Whimmydiddles, Whirligigs, and Capital Punishment: A History of Toys and Games, Being A Partial and Idiosyncratic Exploration of Several Centuries of Developments, Focusing Largely on Europe and North America.

Tyler Calkin

I. Hula Hoops & Human Life

Google’s definition of the word toy is “an object for a child to play with, typically a model or miniature replica of something.”[i] But we know that toys are more complex than this. Toys are for everyone, not just the young: models, miniatures and replicas are as much for adults as they are for children. And the function of a toy extends beyond a moment’s amusement. Throughout history and across cultures, toys have been created to serve as tools for teaching. Indeed, they are almost always instructive in some capacity, eve if they have not been built with a primarily pedagogical intent. Toys are reflectors and propagators of a culture’s ideology, and variably serve as teachers of moral lessons, mathematics, imperialist narratives, class distinctions, and spirituality.

Broadly speaking, European industrialization of the 1800s changed peoples’ perspective of idle time from a natural pause in agrarian calendars to, as urban life came to mean long factory hours, time when one could theoretically be working.[ii] With this shift came a change in the conception of play; it was seen as not only useless but also as an obstacle to productivity. The religious analog of this derision framed play as immoral, and attempted to isolate and insulate children, ultimately attempting to refashion games into moral exercises. This impulse would play out over centuries. Even when 20th century theorists like D.W. Winnicott and Johan Huizinga legitimized play through case studies and cultural criticism, the broader culture primarily accepted play to the extent that it could train children for adulthood. Meanwhile, growing affluence and consumerism propagated toys in the marketplace. Psychoanalytic theory and capitalism dovetailed to push toys toward complexity, variability, newness, and novelty.

To see the state of European toys before this evolution took hold, one can view Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1560 painting Children’s Games. It depicts social play in public space, with the aid of hoops, tops, balls and other toys (see figs. 1 and 2).

Fig 1. Bruegel the Elder, Pieter. Children’s Games, 1560.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Web. 15 November 2015.

Fig 2. Balls and spinning tops, 16th–17th century England.

Colm. Irish Archaeology. 16 February 2013. Web. 21 November 2015. Images © Leicestershire County Council.

In 17th century Europe wealthy families began to desire distance from the vulgarity of common outdoor play, and turned to private tutors. Instead of playing outside, wealthy children would engage in domestic, indoor play. Tutors integrated toys and games into home education, resulting in novel objects like alphabet blocks.[iii] As a pioneering play object, the alphabet block charted a deliberate course into pedagogical toys. As a replacement for social street play it was also likely a tool for preemptive moral conditioning.

Freidrich Froebel’s 19th century educational work jettisoned the tutor and kept the toy. Froebel developed a series of objects for self-directed play intended to be so coherent that upon experiencing them a child would naturally learn about the world. His system of “gifts,” as he called them, also had a spiritual underpinning; Froebel held that “metaphysical unity”[iv] would unfold through his abstract objects. He hoped that not only would children learn about the tangible world, they would be brought into harmony with the universe.

Fig 3. Froebel’s first gift (L), balls, and fifth gift (R), cubes and triangular prisms.

Froebel Gifts™. 2013. Web. 5 April 2016.

The objects progressed from the simple to the complex, beginning with a sphere symbolizing divine universe, and on to cylinders, cubes, and triangles (see fig. 3). By the fourth and fifth gift, children could represent structures from the world around them, such as their neighborhood church. The child’s budding architectural explorations would then continue through a series of “occupations” that taught material skills from paper folding to constructing forms. In 1837 Froebel founded the first Kindergarten and institutionalized his gifts. Although Froebel’s pedagogy was experiential, it was merely metaphorical; toy lessons about the natural world took place inside.

Contrast this with American folk toys like the Whimmydiddle (see fig. 4). The Whimmydiddle requires a direct relationship with the natural world; to make the toy one cuts and carves the branches of a tree into the different parts. Furthermore, one must make the toy oneself for it to truly be a folk toy.[v] A propeller at the end of the toy spins when the smaller stick is rubbed of the larger one’s ridges, making the Whimmydiddle a whirligig, or a toy that spins. The term whirligig encapsulates a deeply rooted form in toys and play—the spinning circle.

Fig 4. Whimmydiddle.

“Gee-haww whammy diddle.” Wikipedia. Wikipedia.org, 25 April 2016. Web. 10 June 2016.

Tops and spinning toys were not solely American inventions. They are globally ubiquitous throughout human history. The Hmong Spinning Game was played by Hmong people in China, Vietnam, Laos and Thailand; India and Pakistan were home to bambaram gaming tops; and Bruegel the Elder painted teetotums in the Netherlands.

One of the most famous spinning circles today is, of course, the Hula Hoop. In 1957 Arthur Melin and Richard Knerr manufactured hoops from a proprietary plastic, which were then marketed and sold by the toy company Wham-O at immense scale.[vi] New and cheap materials, and historically new avenues for advertising (i.e. color television) facilitated a national and international consumer craze in the 1950s and 1960s (see fig. 6), and an enduring popularity today.

Playing with hoops is by no means a modern development (hoop games predate those in Bruegel’s painting by millennia), and Melin and Knerr were both aware of and inspired by hoops from Australia.[vii] They apparently drew from Polynesian culture to name them Hula Hoops, but needn’t have gone that far afield in search of inspiration.

Fig 5. Potawatomi Indian, Gary Wis-Ki-Ge-Amatyuk Jr., performing an American Indian hoop dance.

Wiskigeamatyuk.com. Web. May 1 2016. Photo taken by T.J. Sinsay of Sinsay Fitography, 2009.

Fig 6. People using the Melin- and Knerr-manufactured Hula Hoop.

“The Hula Hoop.” Thoughts from a Buttonmonger. 5 March 2013. Web. 1 December 2015.

While Native American hoop dances are staged as competitive events in today’s Southwestern United States (see fig. 5), they are grounded throughout North America in medicinal, spiritual, and ceremonial tradition. Hoop dances in this tradition are storytelling rituals symbolic of and connected to nature. An Algonquin origin story of the hoop dance tells of a spirit being who “taught his village about the animals by spinning like an eagle in flight or hopping through grass like rabbits or bouncing like a baby deer.”[viii] Communal pedagogy is thus at the core of this practice: by imitating nature, the community teaches itself about the natural world.

European board games used instructive storytelling, but were focused on the lives of people, not the natural world. In 1790, printing technology in London updated the ancient tradition of race games with text and picture in The New Game of Human Life with Rules for Playing: Being the Most Agreeable & Rational Recreation Ever Invented for Youth of Both Sexes. This board game makes no secret of its aspiration: to rescue games, and the children who play them, from that which is disagreeable and unhealthy. The New Game of Human Life depicted the proper stages of an aristocratic life in another step to save children from immorality.

This model became even more openly declarative and moralistic during the next century. In 1840s New England, clergyman’s daughter Anne W. Abbot developed The Mansion of Happiness. An Instructive, Moral, and Entertaining Amusement. Rather than follow a single exemplary life, players navigated vices and virtues in an attempt to reach the Mansion. Board Spaces labeled with traits such as piety, chastity, humility and industry (see fig. 7) allowed players to reach the Mansion of Happiness. But this path was peppered with pitfalls, from idleness to cruelty to breaking the Sabbath, which led players to corresponding punishments: poverty, the stocks and the whipping post to name a few. If players did not reach the Mansion, they would end their decline at the Summit of Dissipation. This board game was likely the first to be commercially available in the US and was widely popular, perhaps because it allowed middle class families to acquire a new leisure activity while also instilling social and religious values in their children.[ix]

Fig 7. Detail of the board for The Mansion of Happiness. An Instructive Moral and Entertaining Amusement.

Courtesy of The Strong, Rochester, New York, USA.

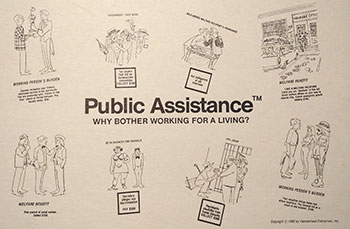

The fear of corruption has not disappeared: even centuries later, social instruction pulses within the heart of many a board game. Two striking examples in 1980 and 1981 carried the tradition of heavy-handed moralizing proudly on their sleeves. The two games comprised the entire output of Hammerhead Enterprises, and they were unsubtly titled according to their targeted political issues: Public Assistance, and Capital Punishment.

Public Assistance: Why Bother Working for a Living? saw players proceed along two parallel tracks through life: as a working person or a welfare recipient. Playing as a worker was intentionally difficult, while a player on welfare received recurring windfalls. On nearly every turn the honest worker was burdened by fees, and overtly sexist and racist scenarios, like “alleged sex discrimination” and “ethnic boyfriends,” somehow always led to further debts (see fig. 8). If a player lost their job their morality and financial wellbeing quickly inverted; a typical “welfare benefit” in this game was picking the pocket of a social worker. Capital Punishment was even more starkly political. Players competed to convict defendants with the harshest possible sentence, ideally the electric chair.

Fig 8. Inside cover of the board game Public Assistance, 1980. Photo by the author.

Even board games that avoided declarative moralizing were nonetheless saturated with ideology. The history of European and American game boards reveals recurring themes of conquest and colonialism, mapped and championed.

Like Froebel’s ball symbolized the universe, board games were often abstract representations of larger environments. Board games like Ringo, for example, used a circle to represent a territory of conflict (see fig. 11), with the center representing a citadel that one player must defend against the other.

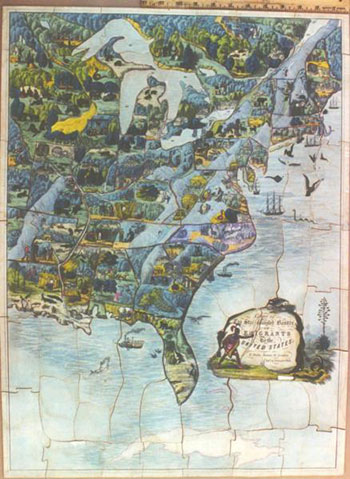

Game makers in the 19th century began using lithograph printing to make more explicit maps. They then cut these maps into jigsaw pieces to make puzzles that taught colonized geography. The western state borders of the Game of the Star-Spangled Banner or Emigrants to the United States (see fig. 9) promoted a positive narrative of emigration and colonization. Some puzzles went even further to represent imperialism, by depicting war scenes as heroic conquests (see fig. 10).

Fig 9. Edward Wallis. Game of the Star-spangled Banner or Emigrants to the United States, ca. 1835.

Bob Armstrong’s Old Jigsaw Puzzles. Web. 2 March 2016.

Fig 10. McLoughlin Brothers. Up the Heights of the San Juan: Our Boys Storming the Blockhouse in Front of Santiago, ca. 1898. The image on this puzzle depicts the Battle for San Juan Heights in July 1898, during the Spanish-American War.

Bob Armstrong’s Old Jigsaw Puzzles. Web. 2 March 2016.

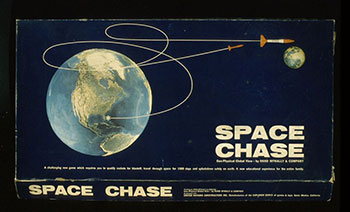

In 1967, Space Chase, in which players competed for space dominance, extended manifest destiny beyond planet earth. Clearly a game of conquest, it was also billed as educational because of its map of earth (see fig. 12) and its essentially accurate representation of multi-stage rockets.

Fig 11. Board for the game Ringo, late 19th century.

Wendel, Bruce and Doranna. Gameboards of North America. Studio, 1986. Print.

Fig 12. Box for the board game Space Chase, 1967. Courtesy of The Strong, Rochester, New York, USA.

The surface appeal of futuristic technology provided late 20th century companies a facile way to market conquest-themed toys. Nintendo’s 1989 Power Glove (see fig. 13) championed, unsurprisingly, power and control. Its packaging promised “total control of virtually any game.”[x] Control in this sense was a technical one, but it invoked the long history of imperialist power embedded in toys and games.

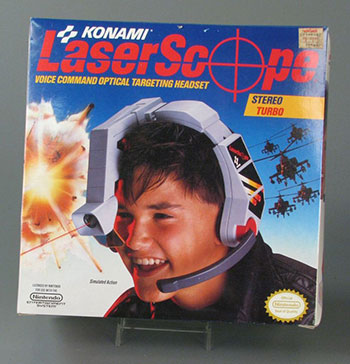

The following year, the association of game controllers with physical power became explicitly violent. Nintendo debuted the Laserscope—a headset with voice command and an eyepiece for weapons targeting—connecting the wearable futuristic controller to the game of war. The explicit war images on its packaging made no secret of this power fantasy (see fig. 14).

Fig 13. Nintendo Power Glove, 1989. Courtesy of The Strong, Rochester, New York, USA.

Fig 14. Packaging for Nintendo Laserscope, 1990. Courtesy of The Strong, Rochester, New York, USA.

II. Patent Models & Monkey Babies

One can also trace the bias and instruction of toys and games through a legal and economic framework. Miniatures, which were not considered toys, played important roles in patent applications and as displays of wealth, sometimes representing toys or leading to their development.

The industriousness promoted by The Mansion of Happiness was mirrored in the growing ranks of inventors in the early United States. The Patent Act of 1836 required models to be submitted along with written descriptions and diagrams for patent applications[xi], as the US Patent Office acknowledged that a working model could convey information more completely than words and pictures alone. Models assisted in court disputes over the novelty of inventions, and the growing need for them led to a burgeoning market for artisans and fabricators. Though these models were not toys, there were many miniature versions of toys made for new applications (see fig. 15), providing curious objects that contained all the qualities of toys without being so in name.

Fig 15. Model for John Brown’s patent application, Improvement in Game Apparatus. Nov 13, 1877. Patent No. 197,091.

Post, Robert E. American Enterprise: Nineteenth-Century Patent Models. New York: Cooper-Hewitt Museum, 1984. Print.

While models may have been useful for inventions, not all of the inventions themselves were useful. In 1869, Commissioner of Patents Samuel Sparks Fisher estimated that only one-tenth of new inventions actually had use value.[xii] Some patent applications had elaborate working models and detailed mechanical descriptions, like Philip Haberstitch’s gear and pulley system for a reversible barber chair[xiii], but no stated or discernable benefit for the user. Free from the burden of utility, these inventions in a sense functioned even more fully as toys, activating imagination and fantasy in the beholder. Baudrillard tells us that “behind every real object there is a dream object”[xiv] that plays actively in our minds.

Though the legal requirement was short lived, ending in 1870, the toy-like quality of the models gave them lasting value as promotional material. A new invention in miniature fascinated and impressed a courtroom or potential manufacturer[xv] the way a toy sparks the imagination of a child.

Mimesis in miniature led to one of the richest fields of toys today. Art cabinets of the 16th and 17th century presented miniature domestic interiors made from precious materials like silver and china, some of which were exact reproductions of peoples’ own furniture.[xvi] Replicating their homes allowed wealthy women to display both their wealth and taste to their peers.

By the 19th century wealthy girls were playing with dollhouses. As generations progressed, many families’ wealth declined, leaving children to play with affordable signifiers of high status.[xvii] Miniature homes thus shifted from class display to class fantasy. And as the 20th century approached, mass-produced dollhouses became available and affordable in the United States, and middle class girls could use them to enact domestic routines and family narratives. Their play rehearsed traditional family structures and roles. Family makeup, class identity and economics status provided a rich backdrop, which children would then integrate into fictionalized play.

The 1840s saw another conflation of adult and child play objects. Both toy makers and stove manufacturers produced cast-iron replica stoves, the former for children and the latter as “salesman samples” for potential buyers. And even some salesman samples ended up in the hands of children, being secondarily intended as a “gift that makes the child love to cook.”[xviii] Here again, the toy instructed the child, reinforcing desired domestic behavior.

Toys can also move the other way, from child’s plaything to adult accouterment. Temari originated in China and Japan as balls of old clothing and fabric given to children, and evolved into a detailed art form for aristocratic women (see fig. 16). And 18th century automatons were dolls for adults: intricate machinery accomplished lifelike movements and feats such as writing or drawing to amuse a mature crowd (see fig. 17).

Fig 16. Japanese Temari ball, ca. 1980. Courtesy of The Strong, Rochester, New York, USA.

Fig 17. Henri Mailliardet. Draughtsman-Writer, 18th century. This automaton had a repertoire of seven sketches and pieces of writing.

Tiffany, Daniel. Toy Medium: Materialism and Modern Lyric. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000. Print. Image courtesy Franklin Institute, Philidelphia.

As we have seen, toys can have complex origins and multiple meanings. Play theorist Brian Sutton-Smith takes this multivalence further, stating that toys simultaneously are and are not what they claim to be.[xix] Though a toy may be crafted to resemble a preexisting thing, say a house or an airplane, it functions as a ludic sign[xx] of that object. Certain unavoidable differences exist between the two. A ludic sign is both negative—a doll does not cry—and distortive—a baby’s skin is not plastic or porcelain. A young child confronts, or is inspired by, these differences during play and uses them to create meaning.

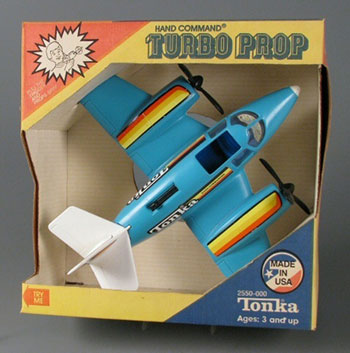

Making a representational toy usually involves shrinking and simplifying the object. This process creates a schematic miniature with exaggerated details that allows for faster object recognition by developing minds (see fig. 18).[xxi] Here lies a difference between the schematic miniature and the exactingly detailed miniature replicas intended for adults (see fig. 19). The former is a toy, the latter a model or collectible.

Fig 18. Hand Command Turbo Prop, 1989. This toy, designed by a retired US Navy engineer, is highly simplified into a schematic miniature. Courtesy of The Strong, Rochester, New York, USA.

Fig 19. 1/48 scale model F-16. The detail and weathering retained on this model despite its reduction in size demonstrate its status as a model or collectible.

“Eduard’s 1/48 Scale f-16 ‘NATO Falcons.’” HyperScale. 16 January 2013. Web. 7 July 2016. Image copyright Matthias Becker 2013.

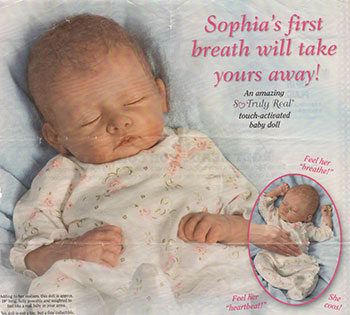

As dolls move back to the adult realm they cross the threshold of toy-ness again. We know that a doll is “not a baby and yet is not not a baby”[xxii] due to its negative semiotic condition. How much more so might a doll not be, or be, a baby if it is not a toy either? Sophia, sold by The Ashton-Drake Galleries, breaches the gulf between human and plaything, “‘breathing’ so peacefully and cooing softly, dreaming little baby dreams”[xxiii] according to her magazine advertisement (see fig. 20). This “living” baby is a playful construction, but in embodying her lifelike qualities, Sophia pushes against the ludic signs of toy-ness. Indeed the same advertisement clarifies that “this doll is not a toy, but a fine collectible.”[xxiv]

In 2012, the line between human and non-human, real and representational, gets even further frayed when Ashton-Drake debuted its Interactive Baby Monkey Doll (see fig. 21). If a human doll implies a parent-child relationship, the Baby Monkey Doll requires a primate adoption model: the doll is no longer merely a stand-in for a human child, but a stand-in for a doll of a human child.

Fig 20. Magazine advertisement for Sophia. Fine print notes that the doll is not a toy, but a fine collectible.

“So Truly Real® Doll.” The Ashton-Drake Galleries. Magazine advertisement, 2014. Print.

Fig 21. Baby Monkey Doll Squeezes Your Finger. The bottom of the web page for this doll notes that the doll is not a toy, but a fine collectible.

The Ashton-Drake Galleries. 2014. Web. 1 May 2016.

Complicating matters further, the “monkey” represented is an Orangutan, a great ape and not a monkey at all. And in a final twist of representational irony, “Orangutan” in Malay means “Person of the Forest.” So this doll that both is and is not a baby, is not a human but is dressed like a human, and is modeled after a “Person” but not called by that name. This doll is trapped in a recursive self-contradiction.

The humanoid companion is nothing new; a toy called Big Loo went on sale in 1963. Also named after a person—this time Louis Marx, the founder of toy company Louis Marx and Co.—Big Loo looked like a robot from science fiction (see fig. 22). Big Loo was the example par excellence of the maximalist attempt to produce an all–encompassing toy: he boasted a battery-powered voice, dart shooter, water gun, flashing eyes, compass, and more. Complexity was his cardinal trait. Standing 38 inches tall, Big Loo even took on the role of playmate. Big Loo stood taller than the average three year old, and thus was too big for a child to easily hold. He could indeed have stood in as an avatar for a friend during solitary play.

Fig 22. Louis Marx and Company. Big Loo, ca. 1963, Courtesy of The Strong, Rochester, New York, USA.

A 20th century trend of toys as gifts increased in popularity as the 21st century approached. In 1984 60% of toys were purchased as gifts for holidays and birthdays[xxv], reinforcing family bonds and contributing to the cultural expectation of celebrations as family affairs. What was more, children were becoming culturally expected to play alone in their room. Toys came to play a foundational educative role for children who largely lacked communal play experiences.[xxvi]

Contemporary to Louis Marx, the creator of Big Loo, the company Creative Playthings made toys of a more countercultural persuasion. The Multiway Rollway, for instance, embodied simplicity and a back-to-basics mentality (see fig. 23). In rejecting the maximalist trend, these construction toys returned to the pedagogical idealism of Froebel’s gifts, and to alphabet blocks before that. The sphere and the cube were immutable ideals under both the spiritual regimes of Froebel’s radical pedagogy and of 1960’s hippy counterculture.

Fig 23. Creative Playthings. Multiway Rollway, 1960-1969. , Courtesy of The Strong, Rochester, New York, USA.

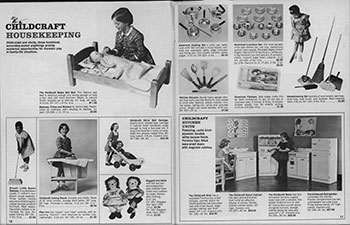

But the formal construction championed anew by Creative Playthings was soon imbued with social values and cultural conditioning. Childcraft’s 1967 catalog featured a “Put-Together Toys” section that advertised construction toys as aides in learning geometry and math (see fig. 24). The value of these toys relied on their promised utility: they could keep a child apace or get them ahead by teaching them during play. Children learned more than mathematics from this catalog; the spread depicts eight boys and two girls. A few pages later, the “Housekeeping” section displays an entirely female cast using household items, such as a young girl holding a broom (see fig. 25). This Housecleaning Set includes an assortment of brooms and mops, described as “real cleaning tools.”[xxvii] More than just toys, these were serious tools with which to practice.

Fig 24. Put-Together Toys section of Childcraft magazine.

Toys That Teach. 1967. New York: Childcraft Education Corp., 1967. Print.

Fig 25. Housekeeping section of Childcraft magazine.

Toys That Teach. 1967. New York: Childcraft Education Corp., 1967. Print.

The November 1979 issue of Psychology Today published “Toy as Machine,” a piece that celebrated the pioneering field of computer toys. This forward-looking essay envisioned a computer toy that “models behavior for the child […] serves as a prod, a corrective, and a sly opponent.”[xxviii] Toys now promised to replace playmates, teachers and even parents, or at least make them obsolete.

III. Useful Conclusion

What can be done with this history? The drive to teach through toys, make play useful, and shape social experience barrels continuously forward, repeating itself in formal variations after variation. If one seeks to critique or resist, it may best be done with models and miniatures of an alternative, rather than in full-scale anti-toy resistance.

Prolific game designer Sid Sackson (1920-2002) left behind extensive notes and unfinished board game prototypes, which now forms the Sid Sackson Collection at the Strong National Museum of Play. The notes reveal a playful methodology and a freedom to ideate critically and beyond the scope of the market. Sackson praises Jean-Marie Albertini’s game Ecoplany, a riff on Monopoly in which players would invariably end in ruin. Sackson conceived of Generation Gap and Silent Majority, whose win conditions are making one’s opponent “feel middle aged and irrelevant” and “giving the best impression of Spiro Agnew,”[xxix] respectively.

There is a gap between Generation Gap and longtime favorite The Game of Life. Games that are enjoyable to consider but difficult to play, much like an endearing but useless patent, are even more toy-like for their impracticality.

Quasi-unplayable games also mirror the planned obsolescence that makes retail toys eventually unusable. Ethical designer Victor Papanek goes so far as to assert that many products are never actually intended to work in the first place.[xxx] Yet strangely, the rich dysfunction or non-function of toys easily perverts into utility. Gag gifts such as canned air can become both savvy market venture, as demonstrated by Vitality Air (see fig. 26), and political artwork, such as Brother Nut’s brick of condensed smog (see fig. 27).

Fig 26. Cans of air bottled in Canada’s Rocky Mountains. Vitality Air’s initial inventory sold out immediately, due to demand from China.

Vitality Air. Web. 7 July 2016.

Fig 27. Brother Nut. Project Dust, 2015. Performance artist Brother Nut spent 100 days walking an industrial vacuum through Beijing, and condensed the collected pollution into a brick.

“Amid Smog Wave, an Artist Molds a Potent Symbol of Beijing’s Pollution.” The New York Times. 1 December 2015. Web. 1 July 2016.

In the context of late capitalism, the supposedly oppositional processes of commodification and one-off prototyping can become entangled by sponsorship. For instance, Kellogg’s commissioned the playfully imaginative designer Dominic Wilcox to create absurd breakfast implements that essentially became advertisements (see fig. 28).

Fig 28. Dominic Wilcox. Cereal Serving Head Crane Device.

“Kellogg’s challenges Dominic to make breakfast more interesting.” Dominic Wilcox. Web. 5 July 2016.

Fig 29. Kenji Kawakami. The Hay Fever Hat™ and Eye Drop Funnel Glasses. The first tenet of Chindogu states that if the invention ends up being frequently used, it is not a Chindogu.

“Kenji Kawakami.” Pinterest. Web. 5 July 2016.

To truly establish an alternative model, even on a miniature scale, one may need an ideology of one’s own. Kenji Kawakami’s Chindogu project (see fig. 29) contains a methodology for object creation governed by tenets that preclude market and use value. The methodology results in objects that live between usefulness and uselessness, which he dubs “unuseless.”[xxxi] Folk-like avoidance of consumerism and a ludic sensibility combine in the International Chindogu Society to form a practice that resists easy consumption, but opens itself wide to play.

Notes

i. “Define: Toy.” Google. Web. 5 February 2016.

ii. Sutton-Smith, Brian. “How Do Children Play with Toys Anyway” draft of address to Culture of Toys Conference, Emory University, c. 1997–1998. Brian Sutton-Smith Papers, collection of The Strong National Museum of Play. Print.

iii. Sutton-Smith, Brian. “Toy future” notes and reference, 1985–1992. Brian Sutton-Smith Papers, collection of The Strong National Museum of Play. Print.

iv. Weston, Peter. The Froebel Educational Institute: the Origins and History of the College. London: University of Surrey Roehampton, 2002. Print.

v. Schnake, Dick. American Folk Toys: How to Make Them. Gloucester: Peter Smith Publisher Inc, 1974. Print.

vi. “Hula hoop.” Wikipedia. Wikipedia.org, 15 June 2016. Web. 25 June 2016.

viii. “Native American Hoop Dance.” Wikipedia. Wikipedia.org, 16 June 2016. Web. 25 June 2016.

ix. “Mansion of Happiness.” The Strong National Museum of Play. 2016. Web. 10 March 2016.

x. “Power Glove.” User manual. Nintendo. 1989. Print.

xi. Post, Robert E. American Enterprise: Nineteenth-Century Patent Models. New York: Cooper-Hewitt Museum, 1984. Print.

xii. Ray, William and Marlys. The Art of Invention: Patent Models and Their Makers. Princeton: Pyne Press, 1974. Print.

xiii. Ray, William and Marlys. The Art of Invention: Patent Models and Their Makers. Princeton: Pyne Press, 1974. Print.

xiv. Baudrillard, Jean. The System of Objects. New York: Verso Books, 2006. Print.

xvi. Stewart, Susan. On Longing. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1993. Print.

xviii. “Rival.” The Strong National Museum of Play. 2016. Web. 10 March 2016.

xix. Sutton-Smith, Brian. “The Role of Toys in the Instigation of Playful Creativity.” Creativity Research Journal, vol. 5, No. 1, 1992. Print.

xxiii. “So Truly Real® Doll.” The Ashton-Drake Galleries. Magazine advertisement, 2014. Print.

xxv. “A Toy Semiotics,” Brian Sutton-Smith, Children’s Environments Quarterly, Spring 1984. Print.

xxvii. Toys That Teach. 1967. New York: Childcraft Education Corp., 1967. Print.

xxviii. “Toy as Machine”, Psychology Today. November, 1979. Print.

xxix. Sackson, Sid. January 5 1970. Diary entry. Print.

xxx. Papanek, Victor and James Hennessey. How Things Don’t Work. New York: Pantheon Books, 1977. Print.

xxxi. Kawakami, Kenji. The Big Bento Box of Unuseless Japanese Inventions. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2005. Print.