Game-play & Design, Society & Community

Larry List

Surrealist theorist Andre Breton observed that “whenever humanity suffers catastrophe…games must be played.”[i] Indeed artists’ interest in game-related work has paralleled WW I & II, the Vietnam War, Afghanistan and Iraq, and current Middle East tensions.

Even a partial list of 20th century artists who have engaged in game–related works is long and distinguished: Andre Breton & Nicolas Calas, John Cage, Alexander Calder, Salvador Dali, Guy DeBord, Julio deDiego, Ugo Dossi, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Richard Filipowski, Alberto Giacometti, Josef Hartwig, Jean Helion, Vilmos Huzar, Carol Janeway, Leon Kelly, Frederick Kiesler, Julien Levy, Man Ray, George Maciunas, Matta, George Marinko, Robert Motherwell, Isamu Noguchi, Hans Richter, Alexander Rodchenko, Xanti Schawinsky, Kurt Seligmann, Muriel Streeter, Yves Tanguy, Kay Sage, Dorothea Tanning.

Contemporary artists who have already made game-related projects in the new millennium include Maurizio Cattelan, Dino & Jake Chapman, Oliver Clegg, Marcel Dzama, Tracey Emin, Tom Friedman, Paul Fryer, Damien Hirst, Glenn Kaino, Barbara Kruger, Yayoi Kusama, Liliya Lifánova, Alastair Mackie, Paul McCarthy, Jeremy Millar, Tim Noble & Sue Webster, Yoko Ono, Gabriel Orozco, Matthew Ronay, Natalie Simon, Lorna Simpson, Diana Thater, Tunga, Gavin Turk, Takako Saito, Guido van der Werve, and Rachel Whiteread.

In light of the current geo-political imbroglios perhaps today’s artists might draw inspiration from past designs, strategies, and performances to respond to the times with new game–related, game-inspired work.

Why Chess

Because chess has long been regarded as “the game of love and war” and has been by far the most popular among artists to work with, much, but not all, of this discussion will be related to projects based upon that game. The character of the six different chess pieces: King, Queen, Bishop, Knight, Rook, and pawn, have a plasticity of identity that has let them be freely re-cast as archetypes specific to each era, culture and aesthetic.

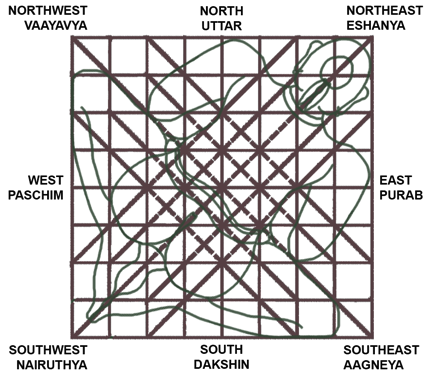

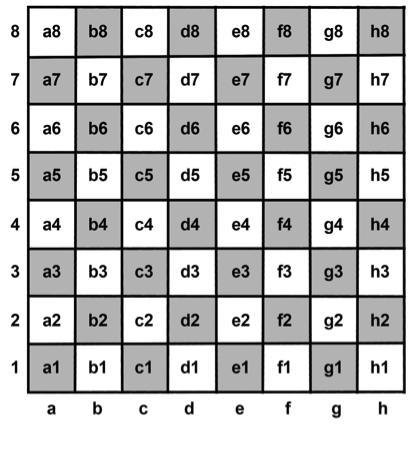

Fig.1. Vastu Purusha Mandala. Drawing by author.

The association of the chess board grid with efforts to define societies and seek community grew from its use in Astapada—a spiral chase game from the 3rd century B.C.[ii] The Astapada grid was derived from the Hindu myth of the Vastu Purusha Mandala, the net-like boundaries traced when a mischievous god was thrown from heaven down onto to the earth.[iii]

A square layout grid of varying numbers of units, it was to be used to establish ideal location and harmonious scale relative to a project’s site and function, be it a residence, temple, civic structure, a sub-division of land, or other spatial construct. Once chess was introduced in Europe around 713 CE this regular grid was slowly adapted there for the layout of buildings, public plazas, and new areas of old cities as they were razed and re-built.

The grid so useful in laying out physical marketplace plazas was then adapted by merchants to organize their accounts and transactions, giving rise to the term “exchequer.” The modern day Excel spreadsheet, with all its variations and complexities, is the mandala’s most recent, elastic reincarnation. For the past 1500 years, the variants of this mandala have proven useful for articulating the sites of love, war, art, architecture, commerce, and accounting.

Designing Society

For many artists, the impetus in game design has been either to accurately reflect the society in which the game was made, or to reflect the designer’s priorities for a new, more ideal society.

At the outset of the 20th century, many of the Dadaist artists were actual combatants in WW I. Max Ernst,

part of an artillery unit, had been wounded;[iv] Andre Breton served as a medical orderly in a military mental hospital; sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Marcel’s older brother, died of blood poisoning from his wounds.[v] As if Gazan or Israeli city-dwellers, all of the artists lived in the middle of contested territories

and were subject to the privations and senseless destruction wrought by warfare.

There was a strong impetus not to let society forget the insanity of war but, also, a strong urge to piece the world back together from whatever was left; to reestablish recognizable patterns of order, behavior, and environment. In the words of collage/assemblage artist Kurt Schwitters “…everything had broken down and new things had to be made out of the fragments…”[vi]

Alexander Calder, for example, fashioned one chess set from wood salvaged from a wrecked house and another set from snippets of scrap metal and wire mounted to slices of a discarded broom handle. Given the same broom handle, with a yearning for simplicity and order, fellow artist Yves Tanguy fashioned an even more minimal set.

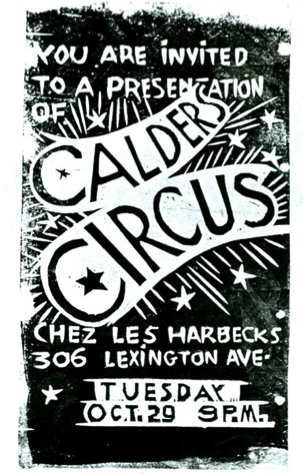

Beginning in 1926, Calder also fashioned an entire kinetic society of his own, Cirque Calder. In Paris and New York, Calder did “pop-up” apartment performances of the dozens of hand-operated animals and characters pieced together from painted scrap material, accompanied by Victrola music D.J’ed by fellow artist Isamu Noguchi. From the outset of his career, Calder’s originality stemmed from “…his determination to respect the role of play…and exploit this element to aesthetic ends.”[vii]

Fig. 2a, b. Alexander Calder. Calder with Cirque Calder. 1929. Calder’s Circus Invitation. 1929. Ink on paper.

Perhaps with bitter memories of his wartime time spent in detention camps and the chess sets made there by pressing together salvia-moistened bread scraps, Max Ernst’s first post-war response was to create chess pieces by literally clenching balls of wet plaster in his still-angry fists.

After escaping Europe in the midst of WWII Ernst created another set by piecing together plaster casts of household furniture and kitchen utensils from a rented summer house, then replicating the pieces as harmonious, unified forms in highly finished hardwoods.

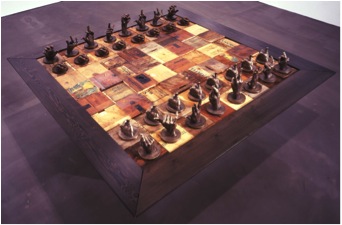

Almost a century later, in post- 9-11 America, when moved to create a chess set, Los Angeleno Paul McCarthy also retreated to the warmth and comfort of his home kitchen. He created pieces from familiar condiment bottles and kitchen supplies then, in an act of “domestic violence” he sawed up his kitchen to make playing boards from the subflooring, and storage containers for the games from sections of his kitchen cabinets, his refrigerator, and other appliances.

Fig. 3a, b. Paul McCarthy. Kitchen Chess. 2003. 32 found objects and resin casts, 64 squares of wooden flooring, standing cupboard.

Chess board with objects: 42 7/8 x 53 1/2 x 53 1/2 inches. Cupboard: 35 5/8 x 49 x 25 inches. © Paul McCarthy. Photos courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and RS&A Ltd, London.

A more hermetic contemporary artist, Tom Friedman, assembled a set from the site of his greatest safety and, conversely, greatest risk, his studio, using miniature tropes of his own artworks as pieces and accenting the set with a 6-pack of beer.

Fig. 4. Tom Friedman. Untitled. 2005. Walnut, maple, pine, cardboard, aluminum, paint, plastic, play-do, glue, acrylic resin, a booger, styrofoam, paper, beer, felt, lead, silver, bronze, and other metals, pillow stuffing, flock, plaster, candy, ink, acetycylic acid, hair, rubber, wire. Chess pieces: tallest piece, 19 inches. 48 x 56 x 36 inches, overall. Edition of 7 with 3 Artist’s Proofs. Photo courtesy of RS&A Ltd, London & Luhring Augustine, NY.

Drawing from childhood sources, British artist Rachel Whiteread has used her collection of dollhouse furniture to create a set that contrasted social class and gender roles by representing one side with working class pieces such as a sink full of dishes, an ironing board, a mop and bucket vs. the leisure class, represented by a sofa, an easy chair, reading lamps and ottomans.

Fig. 5. Rachel Whiteread. Modern Chess Set. 2005. Carpet, linoleum, plywood, beech, plasticized resins, foil, white metal, fabric, enamel, varnish, aluminum wire, brass, ink, chrome, gloss paint, metal wire, foam, fabric handles. Chess Pieces: tallest piece, 4 inches. Board: 1 1/4 x 26 3/8 inches square. Box: 9 5/8 x 29 1/2 x 16 3/8 inches. Edition of 7 with 3 Artist’s Proofs. Photo courtesy of RS&A Ltd, & Luhring Augustine, New York.

Alt-Los Angeleno, Glenn Kaino abandoned the cozy comfort of McCarthy’s kitchen and Whiteread’s dollhouse face-off to address the societal dynamics of the streets of Compton or East L.A. In his monumental 2005 design, Learn to Win or You Will Take Losing for Granted, Kaino used ammo boxes and produce crates to piece together a chess board as a contested neighborhood territory. Bronze-casts from the artist’s own hands express peaceful pop-culture hand gestures on one side with aggressive street gang hand signs on the other.

Fig. 6a, b. Glenn Kaino. Learn to Win or You Will Take Losing for Granted. 2005. 24 x 80 x 80 inches.Chess Pieces: Cast and patinated bronze. Board: wooden produce and ammo crates with stained wood trim. Edition of 3. Collection of Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach; Gift of Paul and Lily Merage. Photo courtesy of the artist, Kavi Gupta Gallery Chicago & Berlin, and Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles.

Community

While game design has offered an opportunity to create a society, game playing has always offered a means to seek a sense of community. Unlike other social aspects of the art world, which may be amorphous, opaque, shape-shifting and duplicitous, game-playing has usually offered a neutral meeting place, an agreed-upon set of guidelines for interaction, equal opportunity, and clear means of evaluating outcomes. Game boards have traditionally been meeting places for strangers as well as rallying sites for friends.

At present, with the synergetic creative power of duos and teams in visual arts, music, script-writing and filmmaking, game-playing is another activity where something new and unique is created across a table by two or more people. However, even games of skill retain an element of chance. One can deploy one’s own resources rationally but the other players’ chance reactions, rational or not, can send the course of creative play off on unforeseeable and imaginative trajectories.[viii]

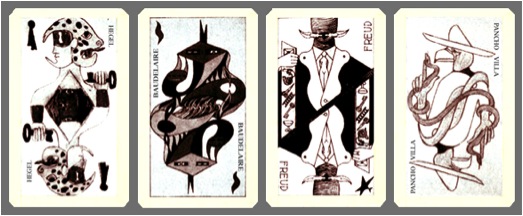

Aside from their fascination with chess, the Dadaists and Surrealists regularly gathered to play communal drawing games such as “Exquisite Corpse,” word games such as “If, Then,” or “Definitions.” In 1940, while stranded in Marseille, awaiting exit visas, (real or counterfeit), to escape WW II, Victor Brauner, Oscar Dominquez, Max Ernst, Jacques Herold, Wilfredo Lam, Jacqueline Lamba and Andre Masson collaboratively designed their own “Marseille Deck,” an elaborate fantasy version of the classic European Tarot cards, Le Tarot de Marseille, produced in that French city, a center of playing card manufacture since the 1890s.

Fig. 7. Exquisite Corpse Drawing.Left: pencil on paper.10 1/4 x 7 5/8 inches.Each section drawn “blind” by one of five different artists.

Courtesy of private collection, New York.

Fig. 8. The Marseilles Deck.1940.Genius: (King) Hegel; Genius: (King) Baudelaire; Magnus: (Jack) Freud; Magnus: (Jack) Pancho Villa. Mixed media on card stock. 4 3/4 x 2 5/8 inches each. Courtesy of private collection, New York.

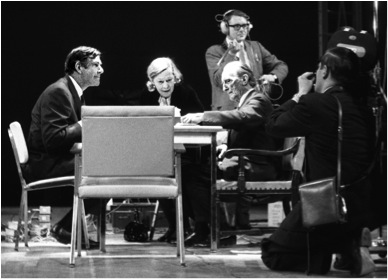

Fig. 9. Blindfold Chess Match. January 6, 1945.At The Imagery of Chess exhibition. Julien Levy Gallery, New York. Kay Sage, Frederick Kiesler, Marcel Duchamp (back turned), blindfold chess Grandmaster George Koltanowski (back turned), Alfred Barr Jr., Xanti Schawinsky, Vittorio Rieti, Dorothea Tanning, and Max Ernst. Photo: Julein Levy. Courtesy of the J.L. Foundation.

Once safely in New York, Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp organized The Imagery of Chess, an exhibition of game-themed works by thirty-two creative people, including artists, architects, composers, librarians, and even a Freudian psychiatrist. The show included a communal “pre-happening happening” blindfold chess event that was part performance, part séance.

From the 1950s onward Los Angeles-born American artist/composer/inventor John Cage, part of The Imagery of Chess show, conjoined Duchamp and the Surrealists’ love of both chess and chance to arrive at new music-composition techniques via Zen Buddhism melding the rationality of the sixty-four squares of the chess board with the rigorously systematic pursuit of chance via the sixty-four hexagrams of the I-Ching.

Fig. 10a, b. Left: Standard chess board with notation. Drawing by author. Right: John Cage. Interpretating the Hexagrams. Detail from Manuscript fragment from Music of Changes. 1951. As reproduced in the unpaginated illustration section of The Roaring Silence—John Cage: A Life. David Revill. New York: Arcade Publishing. 1992. Courtesy of The John Cage Trust.

Games & Fests

Inspired by Duchamp and by John Cage’s “Experimental Composition” music courses at the New School (1957 – 1959), students Jackson Mac Low, La Monte Young, George Brecht, Al Hansen, and Dick Higgins helped George Maciunas and others form the Fluxus art movement.

Individually and collectively, the Fluxus artists set about re-designing society toward “socially constructive ends…such as applied arts…(industrial design, journalism, architecture, engineering, graphic-typographic arts, printing)…” and aiming toward the “…gradual elimination of the fine arts…” and the “art-object as non-functional commodity—to be sold….”[ix]

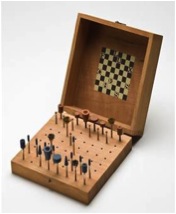

Taking a cue from Duchamp and Joseph Cornell, instead of “fine art” they produced many (pseudo) utilitarian “boxes.” These boxes were offered as modestly priced multiples and quite often contained games that adhered to form but up-ended all expectations of normal play.

![Takako Saito. Flux Chess. [Nuts and Bolts Chess]. 1965 - 1966.](images/larrylist/fig12a.jpg)

Fig. 11a, b. Takako Saito. Left: Flux Chess. [Nuts and Bolts Chess]. 1965 - 1966. Box: wood. 5 x 5 x 2 3/4 inches. Chess pieces: Assorted nuts and bolts, 16 painted white tops, 15 painted black tops. Right: Grinder Chess. C. 1964 - 1965. Box: wood and printed paper label. 6 3/4 x 6 3/4 x 3 inches. Chess pieces: Assorted brass wire and stone abrasive heads on metal shafts. Photos: R. H. Hensleigh. Courtesy of the artist and Reykjavik Art Museum. Now in The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

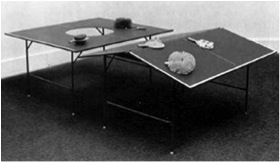

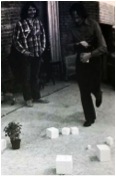

The Fluxus group also staged communal events infused with elements of play and contradiction. From the mid-1960s through the 1970s they held periodic Fluxus Festivals and FluxFest Sports events in the U.S. and Europe featuring a kaleidoscopic array of unorthodox games including: ping pong played on irregular tables with paddles with holes in them or buffering objects on them; soccer played on stilts; and “kick billiards,” with multiple-sized square balls.

Fig. 12. George Maciunas. Fluxus Ping Pong. February 1970. Table: Painted composition board with folding metal legs. Photos: Nancy Anello.

The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Fig. 13a, b. George Maciunas. Fluxus Ping Pong Paddles. As reproduced in the Fluxus Codex, respectively. Left: Can of Water Racket. page 324.

Right: Hole in Center Racket. page 357. Photos: Nancy Anello. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Fig. 14. Takako Saito. Kicking Boxes Billiard. May 1973. Flux Game Fest. New York City. Diverse sizes of folded paper cubes with potted plant. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Larry Miller.

Communal Play Today

More recent game-playing developments in the New York community have included Cabinet Magazine’s Game Series, featuring Hitting Walls: A Day of Handball and Games Day: Triathlon, a Spring 2014 artists’ round–robin backgammon, fooseball, and chess tournament in Brooklyn. The Triathlon event was attended by a widely heterogeneous mix of artists and others ranging from a psychotherapist to a ten year old girl who ended up coming in second! Organized by British artist and game designer Oliver Clegg, the seven hour competition was liberally fueled with free English shepherd’s pie along with Brooklyn Beer and other beverages. The final rounds were played out on fooseball and chess boards custom-designed by the artist.

Fig. 15a. Players get ground rules atCabinet Magazine’s Games Day: Triathlon. March 2, 2014. Brooklyn, New York.

Photo courtesy of the author, artist-organizer Oliver Clegg and Cabinet magazine.

Fig. 15b. Oliver Clegg. One of the artist’s two custom-designed fooseball games, featuring nude figures of the artist (red) vs. his wife (green). Cabinet Magazine’s Games Day: Triathlon. March 2, 2014. Brooklyn, New York. Photo courtesy of the artist-organizer Oliver Clegg, and Cabinet magazine.

At the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, Allison Atgen, Curator of Public Engagement since 2010, has spun out the highly successful Five Years of Public Engagement Series of play spaces and participatory experiences, including Machine Project's Sound Piece for the Hammer Museum.

Fig. 16. Machine Project. Sound Piece for the Hammer Museum. A part of the Five Years of Public Engagement Series.

Photo courtesy of Machine Project and The Hammer Museum of Art.

Playing Music by Playing With Music

The precedents for the Machine Project’s Sound Piece for the Hammer Museum may bounce between the Fluxus Ping Pong and John Cage’s legendary 1968 chess game musical event, Reunion, one of a number of works where game-playing ricochets between the visual and the sonic.

For a Toronto music festival Cage gathered his favorite electronic musician friends, David Tudor, Lowell Cross, David Behrmann and Gordon Mumma together. The auditorium broadcast of the electronic music they produced was determined by each of the chess moves Cage and his chess tutors Marcel and Teeny (Alexina) Duchamp made on a custom electronic chessboard brilliantly designed by Cross. Cage used the event to include the audience into the homey, informal milieu where he and his friends did what they liked best—collaborate on new music, play chess, smoke, talk, and drink wine together.

Fig. 17a. Lowell Cross. Reunion Performance Chess Board. Designed & built for John Cage. 1968. Painted wood & Masonite™ with electronic sensor components. 3 x 16.5 x 16.5 inches. This photo highlights the fact that Duchamp took White, but handicapped himself by removing one knight and placing a quarter coin on the square. Duchamp beat Cage in under 30 minutes. Collection of The John Cage Trust. Photo by Lowell Cross.

Fig. 17b. JOHN CAGE. Reunion Performance. March 5, 1968. Sightsound-systems Festival, Ryerson Polytechnical Institute Theater, Toronto Canada. Teeny Duchamp observing Marcel Duchamp and John Cage playing on board designed & built by Lowell Cross. Photo by Eldon Garnet. © 1968.

Fig. 18. Guido van der Werve. Nummer twaalf, Variations on a theme: The King's Gambit accepted, the number of stars in the sky and why a piano cannot be tuned or waiting for an earthquake. 2009. Piano: Soundboard, piano frame, piano mechanism, benches, ebony, walnut, maple, and chess pieces. Chess piano: 31 1/2 x 27 1/4 x 27 1/4 inches; Benches: approx. 19 3/4 x 11 3/4 x 19 3/4 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist; Galerie Juliette Jongma, Amsterdam; Marc Foxx, Los Angeles; Luhring Augustine, New York, and the World Chess Hall of Fame, Saint Louis. 4k video, Duration: 40 minutes.

The use of a chess board to draw a community together and to be played, both as a game and as a musical instrument of sorts, was imaginatively reprised in 2009 by the Dutch artist Guido van de Werve. Likening the eight square rows of the chess board to eight note musical octaves, the artist fashioned a chess board that mechanically operated as a sixty-four square/sixty-four key piano.

With this, he composed and performed Nummer twaalf, Variations on a theme: …, based on chess notation from Grandmaster Leonid Yudasin. In 2011, for an overflow audience of chess, art, and music enthusiasts at the opening of the World Chess Hall of Fame, van der Werve “played” his chessboard composition as a four-handed piano piece with/against pianist Matthew Bengtson, accompanied by a string ensemble from the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra.

Fig. 19. Hans Richter. 8 x 8: A Chess Sonata in 8 Movements. 1957. (film still). Black and white film. 70 minutes, sound. English.

© Hans Richter Estate.

Playing with Performance and Film

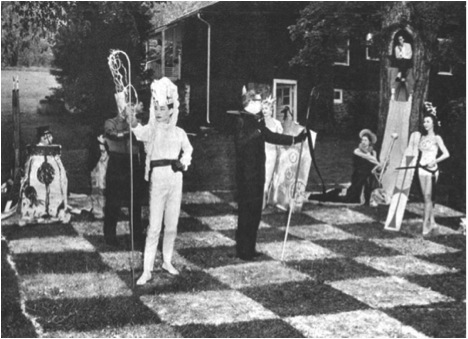

Game-playing experiences and iconography have also been the catalyst for videos and films. Believing that the avant-garde should express “…the playfulness, or whims of artists,”[x] in 1957 German filmmaker Hans Richter invited eight artist friends to each submit an idea for a chess–related scene from which was shot the eight part film 8 X 8: A Chess Sonata in 8 Movements.

This now-classic film is an example of a game-inspired production, communally conceived, acted, scored, and edited by the likes of Jean Arp, Paul Bowles, Jean Cocteau, Alexander Calder, Duchamp, Max Ernst, Richard Hulsenbeck, Frederick Kiesler, Julien Levy, Man Ray, Jacqueline Matisse-Monnier, Yves Tanguy, Dorothea Tanning, and others, with original music by Robert Abramson, Bebe & Louis Barron, Oscar Brand, John Gruen and Douglas Townsend. Described by Richter as “part Lewis Carroll, part Freud,”[xi] participant Matisse-Monnier confirmed that “…it was more about adults having lots of fun than anything else.”[xii]

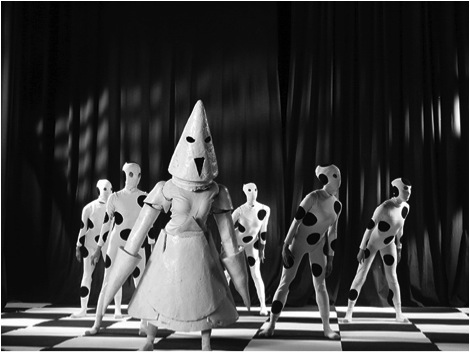

The resonance of projects such as Richter’s 8 x 8 can be felt in works by such contemporary artists as Liliya Lifánova and Marcel Dzama. Kyrgyzstan-born American artist Liliya Lifánova’s 2009 Anatomy is Destiny performance made a gallery installation, The Wardrobe: Game in Waiting, of the garments worn in the full-scale live event. There, thirty-two performers execute moves choreographed by Davy Bisaro to sound by Sebastian Alvarez. Sparked by Sigmund Freud’s theory that “anatomy is destiny,” the movements of the chess piece performers in this game of love and war are based upon those imagined by the artist Arman of a chess game between Marcel Duchamp and his provocative female alter-ego Rrose Sélavy.

Fig. 20 a. Liliya Lifánova. Anatomy is Destiny, The Wardrobe: Game in Waiting, 2009. Mixed-media installation.

Collection of the artist. Photo courtesy of the artist and the World Chess Hall of Fame.

Fig. 20 b. Liliya Lifánova. Anatomy is Destiny. 2009. Performance at the Contemporary Art Museum of Saint Louis presented by the World Chess Hall of Fame. February 15, 2012. Photo courtesy of the artist and the World Chess Hall of Fame.

Fig. 21 a. Marcel Dzama. A Game of Chess. 2011. (film still). 2011. Video projection, 14:02 minutes. Video: Black and white, sound.

Private Collection. Photo courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London. © 2011 Marcel Dzama.

Fig. 21 b, c. Marcel Dzama. Left: The Rook (La Torre). 2011. Polyester resin, fiberglass, plaster, steel, and motor. Private Collection. Right:

The Queen’s Profile or Aux mille tours Revisité. 2010. Graphite, watercolor, and ink on paper in 4 parts. Photos: Courtesy of David Zwirner,

New York/London. © 2011 Marcel Dzama.

With a thorough understanding and appreciation of Oskar Schlemmer’s past Bauhaus dances and the Surrealists’ varied theater practices Canadian artist Marcel Dzama has re-contextualized the genre of a chess game drama for a contemporary milieu. In the process of realizing his film, A Game of Chess, the artist has created a vast, mysterious, yet coherent universe of autonomous artworks in the form of his detailed story-board drawings, collages, dioramas, and sculptural costumes of fabric, paper-mâché, and resin.

All-Consuming Play

Fig. 22 a. Takako Saito. Wine Chess Performance Video of live performance at Reykjavik Museum of Art. March 19, 2009.

Photo courtesy of the artist and Reykjavik Museum of Art.

Fig. 22 b, c. Takako Saito. Canapé Chess Performance Video oflive performanceat Reykjavik Museum of Art. March 19, 2009.

Photo courtesy of the artist and Reykjavik Museum of Art.

The very wine and food that usually accompany artists’ group game-playing have been incorporated into the performance/video pieces by Takako Saito, veteran of earlier Fluxus projects. The artist has acknowledged the Chinese poets’ traditional Jiuling drinking game[xiii] and the 1944 Andre Breton/Nicolas Calas Wine Glass Chess Set, which used six different sized wine glasses to differentiate the six different chess pieces. However, in her Wine Chess, Saito shifts the identity of the pieces from the size of the glasses to the actual wine itself. One player uses sixteen identical glasses with six different red wines against an opponent with an equal number of identical glasses with six different white wines, while in her Canapé Chess pieces opposing arrays of pastries are played, captured and consumed. Here Saito plays with our priority of senses as taste and smell challenge vision in guiding our game-playing.

Playing With the Art World – Designing for the Real World

Artists’ games and gamesmanship has extended even to the suspicion that certain artists have approached the art world as a meta-game. Not surprisingly, Duchamp was one of the first artists to be accused of “career gamesmanship.” Duchamp’s friend and patron Walter Arensberg, suggested that the timing and production of each of the artist’s works was a sequential move in a life-long game strategy, to which Duchamp wryly replied “your comparison between the chronological order of [my] paintings and a game of chess is absolutely right…but will I administer checkmate or will I be mated?”[xiv]

With his repeated critical successes and excellent timing in the marketplace, Damien Hirst has become the new millennium’s prime suspect, accused of somehow “gaming” the art world. Hirst reflected his “take” on society, perhaps suggesting that art and wealth may be drugs in and of themselves, by designing an elaborate chess set ensemble with opulent prescription/designer drug bottle chess pieces of silver and crystal arrayed in a high-tech medical vitrine and laid out on a wheeled gurney-like table.

And, to draw together an art and culture community in London he designed a social “playground” in the form of a fully-functioning restaurant and bar with a liquor license, drinks, and furniture that he named Pharmacy, perhaps a reference to the work by Duchamp.

Now, turning 50, the artist has decided to play with the re-design society on an even larger scale. Here, the ancient Astapada mandala grid from which chess evolved may be applied by an artist again to the layout of a community. Collaborating with architect Michael Rundell and David Lock Associates, Hirst is designing and building “The Southern Extension.” Sited in Ilfracombe, England it is not a game, per se, but an entire town of seven hundred-fifty houses, shops, a primary school, and health care center. As evidence of his level of commitment to the project Rundell told the London paper, The Telegraph, that Hirst aspires to make these houses, “…the kind of homes he would want to live in.”[xv] Of course, Hirst’s critics wonder, once again, “is he really serious or is he is just playing another game with the art world?”

Fig. 23 a, b. David Lock Associates. Damien Hirst’s The Southern Extension. Ilfracombe, England. Two architectural perspective renderings of site. 2012. Illustrations: David Lock Associates, Buckinghamshire, England. © David Lock Associates, Buckinghamshire, England. All rights reserved. 2015.

Whether game designing to piece an ideal personal society together or game playing to communally share a creative exchange of ideas, the play that takes place among artists has always been both valuable and satisfying. As Duchamp explained “it’s a peaceful thing, a peaceful way of understanding life. To play…not just chess alone, but all games, is to play with life…you are so much more alive than people who believe in only religion or art.”

Notes

i. Phyllis Braff, interview with the poet and writer Lionel Abel, New York, unpublished, July 2, 1993. Abel quoted an explanation Breton gave him about game-playing.

ii. H.J.R. Murray. A History of Board-games Other Than Chess. (London: Clarendon Press, 1952).129 – 130.

iii. Niranjan Babu Bangalore, “Vastu Purush Mandala in Home Design and Happiness,” Boloji. March 12, 2006.

http://www.boloji.com/index.cfm?md=Content&sd=Articles&ArticleID=698

Original myth found in the ancient Indian text Mayamatam on Vastu Sastra.

iv. During WW II Ernst had his house confiscated by collaborationists and turned into a brothel while he was imprisoned in (and escaped from) three different detention camps.

v. One of Duchamp-Villon’s last projects, while convalescing, had been the design of a chess set, for which drawings survive in the collection of the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

vi. ‘Kurt Schwitters’ (1930), in “Kurt Schwitters, das literarische Werk”. Ed. Friedhelm Lach, (Cologne: Dumont, 1973 – 1981) Vol. 5, 335.

vii. James Johnson Sweeney quoted by Lipman, Jean. Calder’s Universe. Ruth Wolfe, ed. Whitney Museum of American Art.

(Philadelphia, London: Running Press, 1976) 45.

viii. One recent example of the magnitude of chance and variation still possible in chess, an ultimate game of skill, is that even after 1500 years of recorded chess play globally, some recent sequences of moves played by six of the top ten players in the world at the 2014 Sinquefield Cup Tournament in Saint Louis didn’t register as previously played on any of the major chess computer databases.

ix. Maciuna’s letter to T. Schmit as reproduced in FLUXUS etc./Addenda II. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Collection (Pasadena, CA. Baxter Art Gallery, 1983) 166 – 67; Tomas Schmit, “If I Remember Rightly,” Art and Artists, October 1972, p. 39.

x. Hans Richter, “The Avant-Garde Film Seen From Within”, Hollywood Quarterly, Vol IV, No. I, Fall 1949, p. 35.

xi. H.H.T., “Richter’s Chessboard”, The New York Times, March 16, 1957, p. 16.

xii. Jacqueline Matisse Monnier et al., “Appreciations on Duchamp, Man Ray and Picabia by Jacqueline Matisse Monnier, TJ Demos, George Baker and Kim Knowles”, Tate Ect., Issue 12, Spring 2008.

xiii. Edith Frankel, “Play It Again: An Introduction,” Play It Again: Asian Games and Pastimes (New York: E. & J. Frankel, Ltd., 2004) 21.

xiv. Walter Arensberg, letter to Marcel Duchamp, December 14, 1951, and response letter from Marcel Duchamp to Louise and Walter Arensberg, July 22, 1951, Correspondence Series, Arensberg Archives, Philadelphia Museum of Art Archives. For a beautifully reasoned and complete discussion of this topic please see Francis M. Naumann, “Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess,” in Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess, with Bradley Bailey and Jennifer Shahade. (New York: The Readymade Press, 2009) 1 – 47.

xv. “Damien Hirst to build 500 eco homes.” The Telegraph. February 16, 2012.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-news/9086620/Damien-Hirst-to-build-500-eco-homes.html

Peter Brown. “UPDATE: Damien Hirst-backed plans for Ilfracombe Southern Extension approved.” North Devon Journal. July 30, 2014. http://www.northdevonjournal.co.uk/Damien-Hirst-backed-plans-Ilfracombe-Southern/story-22017969-detail/story.html

Sarah Cascone. “Damien Hirst Gets Green Light to Build City.” artnet news. July 31, 2014.

http://news.artnet.com/people/damien-hirst-gets-green-light-to-build-city-70494?utm_campaign=artnetnews&utm_source=073114daily&utm_medium=email

The author would like to thank the artists and institutions noted in the captions for their permission to include these images. The photographers, sources of visual material, the owners and copyright holders are listed in the captions below the illustrations. Every reasonable effort has been made to supply complete and correct credits; if there are errors or omissions, please contact Larry List at so that corrections can be addressed. Material in copyright is reprinted by permission of copyright holders or under fair use.