To Be Announced

Courtney Malick

Introduction

As we venture into the second decade of the 21st century, it is at times difficult to reconcile the tensions between what remains standard from the past with the complex nuances in thought and technology that complicate contemporary life. Perhaps reconciliation is in fact not desirable after all. If we were to imagine westernized cultures as inhabiting one collective body, whose many limbs are arguably more connected today than ever before by way of the Internet, it seems that that body would be reaching a breaking point, beyond which imminent rebirth awaits.

Through performance, video and new media there continues to emerge a widening selection of contemporary artists whose work addresses the transitions, dismantling and ultimate regeneration of such a social body. While a long lineage of artists exploring this kind of social destruction can undeniably be traced back all the way to Dada if not further, It is the artists, Ivana Basic, Mircea Cantor, Xavier Cha, Brody Condon, Joshua Hagler and collaborators Miri Segal and Or Even Tov, whose work will be examined here, in tandem with a proposed trajectory of a gradual process of social erosion and its subsequent re-germination.

We may envision such an impending break as following an arc, along which this text posits us as currently being in the midst. That is to say that a damaging crack has already struck this social body’s façade, the exacerbation of which has now burrowed deep into its many layers and produced an unfixable rupture. It is at this point in time that we find ourselves as we prepare for—even look forward to—the deconstructing and eventual abstaining from what has been as a form of protest, and a cleaning of the slate that is not unlike the clearing of a forest fire. These seven artists’ work explores ways in which such a breakdown is not only a necessary and recurring part of life, but furthermore how it allows for new systems of communication and identities to function as precarious test sites rather than well-trodden paths relied upon solely for the tenure of their longevity.

Theoretical Influences

The slew of interpersonal, political, economic and ecological disasters that have taken place over the past ten years in particular, along with theories of prominent philosophical and psychological thinkers such as Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Georges Bataille and Walter Benjamin, certainly inform this nihilistic reading of our current moment. Freud’s “death drive”, with which we are by now rather familiar, again relates to the natural example of the forest fire; a disaster that while deadening for individuals, is in fact generative for the future of a larger whole. For insomuch as Freud states that tension is that thing that ruptures the pleasure principle, (originally derived from the principle of constancy, and the antithesis of the death drive, sustained by an unjarring state of predictability and stability), it is, however, precisely an unpleasurable tension, or as he often refers to it, an excitation, that allows for the direction or course of one’s psychic well-being to shift so as to return to a state of pleasure [1]. This is further exemplified in Freud’s reality principle, with which the Ego replaces the pleasure principle for purposes of self-preservation. As Freud states, the reality principle, contending between pleasure and displeasure, “does not abandon the intention of ultimately obtaining pleasure, but it nevertheless demands and carries into effect the postponement of satisfaction, the abandonment of a number of possibilities of gaining satisfaction and the temporary toleration of unpleasure as a step on the long, indirect road to pleasure.” [2]

Jung’s theory of the mid-life crisis is similar to Freud’s, though perhaps more drastic, as he concludes that, “The transition from morning to afternoon means a revaluation of earlier values. There comes the need to appreciate the value of the opposite of our former ideals, to perceive the errors in our former convictions, to recognize the untruth in our former truth, and to feel how much antagonism and even hatred lies in what, until now, had passed for love.” [3] Humanizing and individualizing the destruction of a collective consciousness in this way allows us to more easily see the underlying cyclicality of such a breakdown. For in the same way that we turn to hate what we once loved in our first phase of life, so too we will surely build new monuments around what we come to believe in and love in the second phase, only to later find the untruths that in fact exist therein.

Consideration of Jung’s theory of the mid-life crisis in relation to the destruction of outmoded ways of life also places such a shift within a generational context. In this sense, it becomes all the more obvious that younger generations whose first and most foundational experiences have taken place by way of the Internet, inter-communicative smart-phones and tablets, drastically alters one’s initial understanding of the world at large. Does today’s world appear bigger because we are able to see and know so much more of it, or does our immediate access to it actually render it smaller?

Unlike Jung, Bataille’s theory of unproductive expenditure [4] focuses less on the emotional or atmospheric transitions that lead to such drastic shifts in perspective, but instead on the inherent value of such a loss. In this sense we see a link between Freud and Bataille, who find destruction and waste to be not only necessary and inevitable, but also productive. This is made evident in Bataille’s description of the great individual and collective losses that are accepted as a given within games and sports. As Bataille points out, the similarity to the passions brought about through the relinquishing of conservatism in the playing and participation of sports speaks directly to every individual’s instinctual, if libidinal, death drive, “As much energy as possible is squandered in order to produce a feeling of stupefaction—in any case with an intensity infinitely greater than in productive enterprises. The danger of death is not avoided; on the contrary, it is the object of a strong unconscious attraction.” [5]

With regard to Benjamin and his pre-Marxist exploration of cultural and governmental violence in “Critique of Violence,” it is less important that we understand precisely the differences between his concepts of “mythic” as opposed to “divine violence” [6]. Instead, what is most blatant in his early work is the fact that violence exists in many forms and at all times, and therefore must be contended with and used constructively rather than always attempting its avoidance. Similar to Jung’s inverting of love and hate during a state of transitory mid-life crisis, Benjamin describes the two sides of violence as performing opposing functions, but through the same basic methods, “If mythic violence is lawmaking, divine violence is law-destroying; if the former sets boundaries, the latter boundlessly destroys them.” [7] Here we see that while the dichotomy of Benjamin’s forms of violence on the one hand uphold standards for standard’s sake and on the other hand negate them for precisely the same reason, they are nonetheless equally acrimonious.

The work of Ivana Basic, Mircea Cantor, Xavier Cha, Brody Condon, Joshua Hagler and Miri Segal and Or Even Tov, take on various aesthetic and physical dimensions. However, the basis for their work shares an implementation of hypothetical guidelines and limits onto a particular cast of actants. By setting such fabricated boundaries into motion, they point to the more tangible and applicable social conditions within which their work is made, received and disseminated. These artists have at times also found unusual presentations for the infiltration of their ideas such as online platforms and relatively new organizations whose missions collapse art and theater, science, technology and social media, and other extensions of communication, information and daily life. Their formal, conceptual and professional choices in and of themselves are thus prime examples of an attempt to break down and re-define the role that contemporary art can have throughout the many networks that underlay all cultural production. In this sense we may read integration as a common denominator throughout these artists’ work, and against which destruction thrives.

Fissures: Joshua Hagler, Ivana Basic and Xavier Cha

These seven artists mostly operate independently from one another and are based in various places around the world. When considered in juxtaposition to each other, their work can be understood as marking significant points along our demonstrative arc of collective destruction. This arc begins with the slow breaking down of hundreds of years of cultural and even spiritual conventions and rhetoric. Such an abrasive deterioration is literally conjured in some of the works of the first grouping of these artists, which includes San Francisco based Joshua Hagler’s two-channel video installation, The Evangelists (2012), Belgrade born and New York based Ivana Basic’s performative object and two-channel projection installation, Automata (2011), and New York based Xavier Cha’s performance Body Drama (2011).

Joshua Hagler

Joshua Hagler’s initial ideas for The Evangelists actually sprung from a traumatic incident in which his neighbor started a fire and his apartment building burned down. This disaster caused an inevitable shift in his life, and after a few years of living with the effects, Hagler sought out the neighbor and was eventually able to interview him. After interviewing his neighbor, in which the man described the mental pressure and disease that had caused him to start the fire, Hagler resolved to interview three other men with similar stories as the basis for a new video project.

The four men, each of whom suffered a psychotic breakdown that was brought on by, or coincided with, a religious or spiritual belief or vision, are presented in the video as 3D rendered and animated busts. Their appearance takes on virtual, sculptural forms, which masks their individual differences and the details of their human frailties. They tell their stories in short phrases and then abruptly pause, their eyes suddenly shutting like a robot whose batteries have run out, while another man picks up where the other left off. Between the four of them they sketch a singular and visceral, yet fractured, portrait of a psychic beak. Although each man’s individual story is woven into another’s, the viewer is able to follow their four, separate recollections while at the same time reading their experiences as a correlative episode. The melding of these individual’s breaking points reflects the initial, corrosive stages of the arc of cultural destruction, in whose wake we are by now entrenched.

Ivana Basic

Where Hagler’s work intimately explores personal schisms that we may perceive as symptomatic of a wider reaching and underlying social boiling point, Ivana Basicʼs multi-faceted installation, Automata, carves open the space for total obliteration. Basic describes Automata as a performative object created to be self-destroying through the process of slow breaking. The work focuses on human physicality and its limitations, as they are perceived through various social contexts. Automata is constructed of eight solenoids that are implanted inside a white, blob-like object made of plaster, which pound at the inside of its walls in order to break it open. At the same time, a microscopic camera, also placed inside the blob, records the breaking. The live-feed of this process is then projected on a nearby wall.

This animate object can be seen as a stand-in for consciousness en masse due to its lack of distinct form and its undeniable corporeality as it conjures the form of the head of the penis. Further personifying the blob, it also contains sensors that alert it when anyone approaches too closely, stopping the pounding of the solenoids temporarily, while the video projection automatically switches from the interior of the blob to a shot of its exterior, which includes a projection of the lurking viewer. Once the viewer moves away, the pounding continues and the projected feed returns to the tapping of the solenoids. The total destruction of the blob, which takes approximately three days to complete, results in its crumbling to pieces. Automata exemplifies a kind of reflexive destruction that comes from within. In fact, when outside forces weigh too heavily upon it, the destructive process is paused. This aspect of the work is crucial in that it renders the blob conscious, and even more importantly, independent.

Xavier Cha

Xavier Cha’s three month performance, Body Drama took place in the lobby gallery at The Whitney Museum of American Art in the summer of 2011. During that time, performers cast by Cha appeared to be losing their minds. The performers, who are also actors and performance artists themselves, were instructed by Cha to ignore visitors to the museum and focus on expressing an indescribable and acutely intense fear or anxiety. The catch was that while producing this uncomfortable bodily reaction, alone in the gallery, each performer was fashioned with a cumbersome and rather large camera strapped to their body and pointed directly in their face. This contraption is often how close-up, edgy camera work in horror movies is achieved. Yet, the imposing camera-harness created a palpable divide between the performerʼs incredible ability to remain fully enveloped in their fear, and the inability of the viewer to abandon their disbelief when peering in on them during one of their freak-outs. Further complicating this refractive work, once the performance has run its course, the footage captured is immediately projected onto a floating wall that divides the gallery into two halves.

Not so unlike Basic, with Body Drama, Cha allows us to see ways in which we collectively self-destruct through our obsessive and compulsive role as simultaneous voyeur and performer. Perhaps in Cha’s work the destruction at hand is not as directly inflicted on the self as is blatantly the case with Basic’s Automata, but regardless, Body Drama alludes to the ways in which we submit ourselves to all kinds of scrutiny. As a result we impose more and more pressure on our own culture and its standards. Senior Curatorial Assistant of the Whitney at the time, Diana Kamin, accurately describes ways in which this incessancy plays out on a wide social scale in her essay, “Xavier Cha: Body Drama,” which accompanied the performance, “With Body Drama, Cha has created a situation that reflects fractured contemporary life, in which virtual interactions via social media and a seemingly infinite flow of information, mediated through myriad screens and channels, continually offers portals into previously inaccessible viewpoints. [The work] disorients us because it feeds into the conflict between our powerful instinct to understand the world more fully through multiple perspectives and the anxiety produced by the constant stream of options.” [8]

Body Drama clearly raises all kinds of questions about the motivations of the role of performers as well as those of audiences in all social situations. However, it is especially important to recognize that this work also calls drastic attention to an oxymoronic condition similar to those brought up in the work of feminists such as Judy Chicago and Hannah Wilke, among many others, when they revealed that the beautifying products and rituals that claim to breed confidence, in fact often contribute to emotional pain, embarrassment and a splintered sense of self. With Body Drama, Cha brings these frustrations—a backlash of the fulfillment of our own unhealthy desires, which are by no means limited to women or feminist issues—to the fore.

Void-Making: Mircea Cantor

Later phases of destruction that retract from obstructive violence and turn to abstinence, lead to an eventual state of blankness. This state is ever present and intoxicatingly so, in much of the work by Paris based Mircea Cantor. His video Tracking Happiness (2009) is one of many of his works that leaves viewers craving less rather than more. Cantor’s work often refers to something that is coming next, or the negation of something common or familiar. Again, integration proves to be the nemesis of an axiomatic decimation. His ability to turn something familiar on its ear, so to speak, often produces a pluralizing that alone changes its meaning. His project Double Heads Matches (2002) does precisely that. The basis of the work is a simple documentary-style video investigation of a match making factory in the artists’ native Romania, but then in a twist, Cantor commissioned the factory to create 20,000 boxes of double headed matches that can burn at both ends—the old “candle” idiom clearly referencing factory conditions more generally—while at the same time doubling something that is so ordinary a product that we take it entirely for granted.

|

|

|

Mircea Cantor, Untitled (unpredictablefuture), 2004 |

Mircea Cantor, No Title (The New Times) 2009 |

In an essay written in accompaniment to a screening of video works by Cantor at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2007, art critic and University College London Art History Professor, T.J. Demos sees Double Heads Matches and other of Cantor’s videos as the inverse of a political protest, which challenges even the very language and practice of resistance itself. Demos writes on another of Cantor’s videos, Nulle part ailleurs (Nowhere, Elsewhere), which stitches together a vast array of commercial footage for vacation resorts culled from the Internet, “Nulle part ailleurs shows one aspect of our current system of socio-political reality, according to which the whole social body—down to every individual and its biological and corporeal existence—is comprised of power’s machine; that is, of the diffusions of diverse and subtle technologies of social control, such as architectural design and the patterns of commercialized leisure that regulate and discipline life.” [9]

|

Mircea Cantor, Double Heads Matches, 2002-03, video stills and installation |

However, unlike the work of Hagler, Basic and Cha, Cantor’s installations and videos leave audiences with a sensation of retreat rather than attack or expulsion. Tracking Happiness is a prime example of just this sort of muted protest. The performance that the video captures takes place in a conceptual vacuum, furnished only with a white background and white sand. The video depicts a kind of cleansing ritual carried out by six dark-haired, bare footed women, all dressed in the same white skirts and shirts. They form a circle and slowly pace clockwise. Each woman carries a broom and sweeps away the footprint left by the woman in front of her. Accompanied by a celestial soundscape, the work evokes a sense of serenity that can come with total negation, as the women form a sort of mechanism that exists without leaving any visible trace. It is also significant that the performer’s act of deletion does not include men, emphasizing the feminine reclusion to that of the masculine protrusion and denying this fictional scene any chance for reproduction.

Tracking Happiness video at: http://vimeopro.com/yvonlambert/mirceacantor/video/32563064

Test Sites: Miri Segal and Or Even Tov and Brody Condon

Lastly, a regenerative period in which experimental new forms of thought are tested within microcosmic, ephemeral frameworks are brought to our consideration in the collaborative project Future Perfect (2010) by Tel Aviv based Miri Segal and Or Even Tov that includes the video Sergey B., an accompanying 3-D printed sculptural object, Gmind and a video advertisement titled Gmind Mobile, and New York based Brody Condon’s performance and video Future Gestalt (2012). Both Segal/Tov and Condon postulate the context of their work, and therefore of their audience as well, into a time that does not necessarily have to be understood as the future, but rather as simply ulterior. Though it plays out in very different ways, these artists share an interest in gaming structures. For Condon these include Live Action Role Playing (LARP-ing), while Segal’s work, much like that of Chinese artist Cao Fei, has explored, among other realms, the virtual realities of Second Life. In this sense their work, more so than Hagler’s, Basic’s, Cha’s and Cantor’s, asserts our current culture’s heightened value of the template. Curiously, inasmuch as the concept of the template is at work here,both Segal/Tov and Condon complicate the issue by using it as a productive means to express their ideas, while at the same time its inherent rigidity exposes the very socially imposed limits that their work often aims to thwart.

Miri Segal and Or Even Tov

Miri Segal, who, not surprisingly, received her Ph.D. in Mathematics before becoming an artist, uses her video and new media installations as an opportunity to force viewers to question their reliance on their own modes of perception. The instability produced therein purports unsettling environments. However, in Segal’s collaborative project with Tov, Future Perfect, which includes the video installation Sergey B., (admittedly named after Sergey Brin, inventor of the Google Glasses), a 3-D printed template for the wearable computer headpiece, Gmind, and a video advertisement for the product titled, Gmind Mobile, they are not questioning perception, but rather inevitable technological interventions that lay merely in the distance. Sergey B. takes the form of an online, interactive live commercial with a man named Sergey B. as its host, who presents Gmind, a new wearable headpiece computer from the company Gooble, (in exactly the same font and primary colors as the Google logo, no less). Gmind is entirely activated by the user’s thoughts, its screen can instantaneously be turned on and off and is displayed across the surface of the user’s retina. The accompanying advertisement, Gmind Mobile, demonstrates how the computer works by showing audiences the perspective of the user.

Here Segal/Tov make direct reference to technologies that are being integrated with brain function, which are already beginning to emerge today (see this Ted Talk lecture and demonstration by Emotiv Lifescience Founder and CEO, Tan Le).

In one sense this kind of brainwave-guided technology may be considered a glimpse into our plausible future that would drastically change interpersonal communication indefinitely. In another way, this work and the fact that this hypothetical device is already being developed, may be seen as a potential threat to humanity as we know it, and in this way, Future Perfect complicates the linear trajectory of the arc that connects destruction and metamorphosis. Indeed, the believability of Sergey B., particularly in relation to the Youtube commercials for Google’s new computerized glasses is perhaps what is most intriguing about the work.

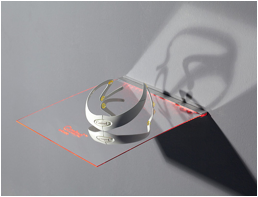

|

|

|

Miri Segal and Or Even Tov, Gmind Mobile, 2010 |

Miri Segal and Or Even Tov, Gmind, 2010 |

The installation of the sculpture/prototype for Gmind also calls important attention to the current flourishing of 3-D printing in all aspects of design, medicine and architecture, which is being discussed as a revolution in technology as significant as the advent of the printing press in 1440. With such evocative and yet haunting glimpses of what life could potentially be like with the integration of these kinds of immersive technologies, Segal/Tov seem to be teasing their viewers. Similar to Cha’s work, with Sergey B., Segal/Tov force us to ask ourselves if we are embarking on an exciting new world of convenience and ultimate connectivity, or if the work represents the false hopes of a culture collapsing under the weight of its own dependency on materiality and its relentless need for speed, the devastating effects of which are palpably felt by our natural resources as they continue to weaken in retaliation against us.

Brody Condon

Brody Condon’s practice explores fantasy and LARP-ing, in which performers are at times referred to as “players” and wherein Condon takes on the role of the ringleader or Director. In this way, his work inhabits an undeterminable time and place that follows a hypothetical breakage, which thus allows for new forms of relationships and communities to thrive. More so than Segal, Condon is operating outside of an even conceivable notion of what life might look like any time soon. Instead performers are given sets of specific yet abstract confines and objectives within which to interact, not so unlike those that Allan Kaprow imposed upon participants in his workshop-like happenings in the late 1970s. Certainly we can see the influence of the group therapy boom that took place in the 70s throughout much of Condon’s performance-based work. In fact, Condon himself has described Future Gestalt as “a 70s group encounter session set in the far future.”

|

Brody Condon, LevelFive, 2010, |

Set beneath Tony Smith’s overarching permanent sculpture Smoke (1967) at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Future Gestalt’s cast of six performers, each swathed in the same colorful, draping robes, slither, swarm and spin amongst one another in response to heavily vo-coded instructions being given by the group’s leader, Condon, sitting just outside the frame of action. At times they interact intently with Smith’s sculpture, whispering barely recognizable confessions of some sort into its smooth black surfaces. Moaning, reverberation and clickings of the tongue are laid over the dialog, complicating the viewer’s ability to distinguish between what passes as verbal communication as opposed to atmospheric affectation.

In Future Gestalt we can certainly see applications of Jung’s theory of the psyche’s mid-life crisis at play. As viewers, we have little if anything at all to bring with us from our previous experiences to use as referents to help us situate this work. It reminds us of the kind of break with reality experienced by the men in The Evangelists, and it could only possibly take place after the kind of explosion of concrete “truths” that we see in Automata and the resulting blankness found in Tracking Happiness. Like Segal/Tov, Future Gestalt seems to be more an advertisement of sorts, featuring potentialities for ways of life, rather than anything resembling an immediate reality. Nonetheless, more so today than ever before, the future and its template-inspired projections represent our current state and this in turn allows us to respond to them with increasing ease.

Condon’s work is, at its core, most often about the formation and navigation of boundaries. However, by primarily presenting his ideas via performance, rather than sculpture or installation, such boundaries are able to remain not only relatively fluid by way of individual interpretation, but also temporal and impermanent. In this way, while Future Gestalt certainly connotes a sense of the nature of human communication perhaps 100 years from now, the work itself functions much more like a frame within which this particular performative iteration has manifested with performers behaving in a certain manner, rather than a prescription to be followed precisely.

Synthesis

While it may seem pessimistic to diagnose the well being of our culture as currently crumbling before our eyes, as we see through these artists’ practices and in the works of Bataille, Benjamin, Freud and Jung, there is something liberating about one’s own demise, particularly when it is self-inflicted. What is important to take note of with regards to Basic, Cantor, Cha, Condon, Hagler and Segal is that their work, in part due to its performative underpinnings, resists definities, circumscription, and belief systems altogether. Though a viewer’s interpretation comprises a large part of the meaning of any work of art, a painting or a sculpture is definite in a certain sense—it is unchangeable. In these artists’ works, even something as resolute as a video, (particularly in the cases of Segal and Condon), conveys meanings beyond its material form, thus signifying one of an infinite number of potential expressions of a foundational set of intersecting questions and postulations that in fact make up the very essence of the work.

We need not deny the fact that to believe in the rejection of something we have come to know as being as primal as the formation of beliefs, is in itself the creation of a new belief system. However, we can see a distinct dichotomy between religious beliefs, for example, and those of someone like Cantor, whose work promotes, in a certain extremist sense, nothing at all. The shifty quality of these artists’ works clearly speaks to the subliminal, DIY kinds of environments and formats, whether physical, virtual or mental, in which so many people today not only choose to work and communicate, but in which they are often expected, even forced, to do so. The benefit of such demands on our daily modes of life is that complex technological forms of communication are inclined to multiplicity and hybridity—words that in their most traditional sense directly contradict the steadfastness associated with belief systems and the exclusive communities that they often form.

While some of these artists’ works have here been aligned with the beginnings of an immense annihilation, others the cleansing state that ensues, and still others with the tinkering of unprecedented structures, each of these works allows for various interjections of chance. In part these allowances are made possible by the composite anatomy of the works themselves. Rather than representing one thing and being made mostly of one thing, these works are both formed by many, at times inharmonious parts, and also point to multiple, at times diverging modes of thinking and being. This can be no accident. Instead, it is likely that this kind of propensity for indecision is the result of an incurring age in which the present is endlessly tripping over the impatient feet of the future, whose M.O. is the ever intensifying precision of simultaneity.

Whereas hundreds of years ago what we may have desired was concise, definite answers and proven paths to follow, believe in and pass down to others, today our lives demand more and more malleability, making the notion of a strong belief or conviction almost obsolete. We see this even in the “faith” that we put into the technological devices that we severely rely upon and arguably form physical attachments to, which we all know are regularly tossed aside for upgraded and new versions. These drastic transitions in the ways that we interact with one another and document and organize our lives are designed to speed up the general pace of life, and with that speed comes a slipperiness and lack of accountability that must be examined. It is in this spirit that these works of art are presented here. In this sense, these artists’ work, if they stand at all, intentionally stand on the most unstable of legs, professing little if any definitive claims. Yet in their fragility, they put forth a new kind of artwork, one that can be slipped into many different contexts, hopefully even some that we cannot yet envision.

End Notes

1. Freud, Sigmund, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Hogarth Press Limited, Toronto, 1922, pp. 7.

3 Jung, Carl Gustav, Two Esays on Analytical Psychology, Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 7, 1972 http://outlawpsych.com/outlawpsych/?p=3041

4 Bataille, Georges, The Notion of Expenditure, 1933

6 Benjamin, Walter, Critique of Violence, 1921 http://anthropologicalmaterialism.hypotheses.org/1040

8 Kamin, Diana, Xavier Cha: Body Drama, The Whitney Museum of American Art, 2011,

9 Demos, T.J., Mircea Cantor: The Title is the Last Thing, Philadelphia Museum of Art, February 2007

10 Kaprow, Allan, “Some Recent Happenings,” Great Bear Pamphlet, Something Else Press, 1966. “A Happening is an assemblage of events performed or perceived in more than one time and place. Its material environments may be constructed, taken over directly from what is available, or altered slightly; just as its activities may be invented or commonplace. A Happening, unlike a stage play, may occur at a supermarket, driving along a highway, under a pile of rags, and in a friendʼs kitchen, either at once or sequentially. If sequentially, time may extend to more than a year. The Happening is performed according to plan but without rehearsal, audience or repetition. It is art but seems closer to life.”